Rampage is a documentary made by George Gittoes.

Gittoes has been a war photographer for decades and made his first documentary, A Soundtrack to War in 2004. It looked at the music listened to by the American army troops in Iraq, and Rampage leads directly on from that by examining the lives of the Lovett brothers in Miami.

Elliot Lovett was one of the standout soldiers in the first documentary; a wannabe rapper who was little fazed by the violence in Iraq due to his upbringing in the Brown Sub low rises of Miami.

Rampage follows Elliot home to meet his brothers Marcus, Alton and Denzell, their family and friends and to see what life is really like in the ghettos of the USA.

Rampage throws up a lot of conflict. Not just in the situation faced by its subjects, stuck in the rut of gang violence and poverty, but within the issues raised in the film.

On the one hand it is crushingly depressing to see so many people seemingly chained into the vicious circle of ‘urban’ culture, of macho posturing and the urgency of seeking a quick, dangerous buck over any planning. It is astounding how everyone in the neighbourhood seems so accepting, let alone resigned, to the horrifically violent culture that they live in; granma Lovett looking on with fondness as her grandson Marcus tells everyone just how he would torture and murder anyone that messed with his family. Here the conflict comes from condemning the eagerness to violence, but is it hypocritical to judge when Marcus and his neighbours are all under constant danger of death? Marcus himself is assassinated by a teen hitman during the course of the documentary, punctuating the different situation they all face. It’s one thing to criticise the reverence for violence in the ghetto culture, but from a position of relative safety it is hard to dictate how to live.

The area is more dangerous than Iraq, with the local professor of criminology estimating that 1 in 8 young men die violent deaths before their 23rd birthday, which the wounds of the majority of the Lovett brothers’ friends attest to.

On the other hand you have Gittoes, who breaks with documentary tradition and steps in to try and get Denzell, the youngest Lovett, a record deal in New York and a life out of the Brown Sub.

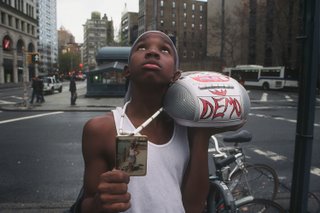

Denzell is turned down by all the record company men as he is told that he is too young to rap about what he is living everyday, as if the horrific reality of gangland life is only fantasy.

But then you have the problem of Denzell’s rap: why would he want to continue reliving such a hell? Why would he want to dwell on the violence and petty squabbles for dubious respect? The fact that Denzell should be able to rap about the drug deals and murders that he has witnessed first hand doesn’t address how are his stories any different to the endless run of MCs year after year telling you how their skill with a mic is only surpassed by their skill with a 9?

It’s a weird paradox, the hope that the promotion and glorification of the stereotypical gangsta lifestyle will help Denzell and his family to stop living it.

Then you have that subjective element of Gittoes getting involved with his subjects. It seems that becoming the focus of filming may have made the Lovetts a target for rival gangbangers and guilt for his role in the death of Marcus spurs Gittoes into doing his utmost to help out Denzell. Would Marcus still be alive? Would Denzell have received as much exposure?

Again, it’s easy to blame those stuck in the projects for sticking to the self-fulfilling prophecy of a violent thug life, but without having to live it perhaps it isn’t fair to judge.

After years of gangsta rap culture played out through music and movies it is easy to see it as fantasy, clichés so recognisable as to be easily dismissed as fiction, but the look on Denzell’s face during his brother’s funeral brings you back to reality with a crash.

Rampage is potent stuff and serves as a reminder that even if the mess in Iraq gets to a point peaceful enough so the GIs can go home, there are old war zones still festering in the heart of America, but there are no media campaigns to end these wars.

Not having learnt the wonderful ability of posting videos within the page as if altering the very fabric of existence, I furnish you with a link to the Rampage trailer: Depress mouse button once pointer icon has alighted 'pon these words

-

Whilst on the subject of questionable reality, I found Borat quite an odd film.

A weird mixture of the usual skits lifted straight from the TV shows where Mr. Cohen has one of his characters perplex ‘real people’, and bizarre scripted moments hanging around a mutant plot, it is sometimes hard to work out where the reality ends and the fiction begins.

All of the moments that seem to involve unscripted people tend to be straight lifts from Borat or Ali G sketches, and whilst it is alarming to receive the apparently genuine thoughts of honest-to-goodness Aymericans, the addition of fiction into the mix only dulls the impact. It’s easy to believe that people were paid to say they wanted gays killed, or that people only acted so astoundingly confrontational in New York to further the film, rather than being filmed unawares. And if the shock element of watching people believe that the character of Borat is a real person or revealing their hidden controversial thoughts has been dulled, then Borat the movie has to rely on comedy for a backup

The film does have it’s moments, but I’ve never been one for the ‘cringe’ school of comedy so it’s enjoyable but there’s little in the way of belly-laughs outside the more bizarre moments and now-familiar bad taste gags.

-

The third film I’ve seen is a slightly less chaotic portrayal of the United States.

Little Children is a film of depths.

Deceptively smooth, it plays out like this year’s American Beauty, depicting the ennui and desperate yearnings of American suburbia, far removed from the turbulence of Rampage.

With a steady pace and flattering photography, it could be forgiven for appearing staid, but it crackles with the energy of the characters who seek a metaphorical escape from surburban restraint.

Of course, these themes have been covered as intensely as the OJ trial by French and Spanish cinema for decades, but American cinema rarely affords itself the opportunity to suggest that adultery may not be such a sin and that paedophiles may have lives beyond the monstrous.

Kate Winslet continues her taste for getting nekkid and is used to taking less-than flattering roles, here playing a bookish and alienated housewife, but here role is brave for the portrayal of a mother who seems less than enamoured with her little miracle. It’s a move virtually unheard of outside the horror genre, but brings some welcome authenticity to the film.

In a less challenging but still comparatively rare role, Patrick Wilson plays a house husband, a man not defined by his career (or lack of) and with little interest in passing the bar exam he keeps failing.

Both characters share a distance from their other halves, finding a bond with each other in their afternoons together with their children, a bond which soon develops.

All the while a flasher of kiddies has been released from prison and someone has been fly posting the neighbourhood with warnings.

The character is both monster and human, Jackie Earle Haley presenting a suitably pale and wizened figure, with a self-awareness of his less than normal tastes (Jane Adams playing one unfortunate on the receiving end, continuing a bad run of things from Happiness). But he also has a world outside his desires, a factor usually ignored in most cinematic portrayals.

-

I Still Know What You Did Last Summer is notable for having Lamb play over the ending credits, a feat matched by last week’s episode of Torchwood which again was a strangely pleasing mix of interesting ideas and slightly clumsy execution.

No comments:

Post a Comment